Low level text layout kickoff

This post is to announce a new Rust library for low-level text layout, called “skribo” (the Esperanto word for “writing”). This has been a major gap in the Rust ecosystem, and I hope the new crate can improve text handling across the board.

Multiple shaping engines

The skribo library doesn’t do shaping itself; it is basically a glue library on top of an actual shaping engine. Most users will use HarfBuzz for this, the industry-standard library. However, a goal for skribo is that it abstracts over the details of the shaping engine. Other choices include platform text (DirectWrite on Windows, CoreText on macOS and iOS). Also, if and when a Rust-native shaping library emerges, we want to make it easy to switch to that.

The choice of whether to use HarfBuzz or platform shaping is a tradeoff. Using HarfBuzz means more consistency across platforms, and thus an easier testing story. Using platform text means more consistency with other apps on the platform, and less code in the critical path (so shorter compile times and smaller executables).

Shaping is essential to complex scripts such as Devanagari and Arabic, but important even in Latin to improve quality through ligatures and kerning. On the left is text without shaping (rendered with Cairo’s “toy text API”), on the right properly shaped text (rendered with DirectWrite):

Expected users

This work is funded by Mozilla Research to be used in Servo. Doing text layout for the Web is a very complex problem. The higher level representation of rich text is very tightly bound to the DOM and CSS. All that logic needs to live in Servo, with the lower level providing a clean interface to lay out a span of text with a single style and a single BiDi direction.

The second major use case is piet, the 2D graphics abstraction I’ve been working on. Currently for the Cairo back-end piet uses the “toy text API,” which is of course inadequate. The idea is that skribo handles text layout for Cairo and all future low-level drawing back-ends (including any future back-end using WebRender or direct Vulkan drawing). A requirement for both Web layout and text editing within GUI apps (including potential front-end work for xi-editor) is fine-grained measurement of text, including positioning of carets within text as well as width measurement of spans of text.

Additionally, just about every game engine currently being implemented in Rust uses a simplistic approach to text layout, just looking up each codepoint in the font’s cmap and then using its advance width to build a layout. I want to encourage all such engines to migrate to skribo, and want to make that experience smooth. In short, if you’re using rusttype, you should consider using skribo.

Problems to solve

Aside from being glue abstracting over implementation details, the main actual problem skribo addresses is choosing fonts from a “font collection”, which is similar to a “font stack” in CSS. In general, this will contain custom fonts as well as a set of system fallback fonts. This might seem like a relatively simple problem, but there are tons of tricky details – no doubt, I’ll write a blog post on just this topic.

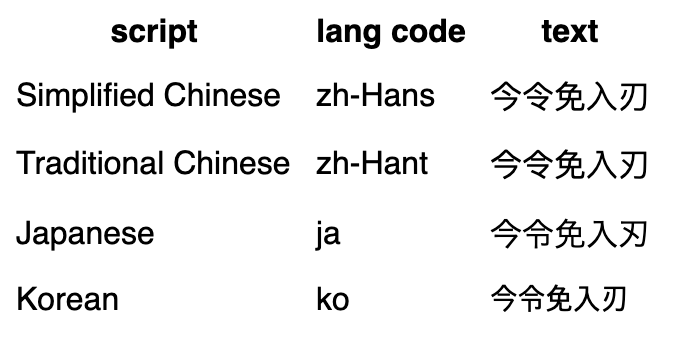

Another major problem is making sure locale information affects layout properly. One of the most important to solve is Han unification, which is the fact that Chinese, Japanese, and Korean share unicode codepoints even though they can be considered different scripts. Often, they should be rendered with different fonts (meaning that Unicode coverage is not the only criterion for selecting fonts). Alternatively, fonts like Source Han Sans have variant glyphs for all CJK languages, and use the “locl” OpenType feature to select them. A good layout library handles both, transparently to applications.

Here’s a visual example of the effect of locale on the rendering of CJK text. In all cases, the ideographs are the same sequence of Unicode code points:

Other problems within scope are figuring out logic for “fake bold” and “fake italic” when the font collection doesn’t provide true versions, as well as adding letter-spacing.

Looking forward, font variations affect layout, so one of the goals is to plumb this through to the underlying shaping engine, where supported.

Performance

Unfortunately, OpenType shaping is a fairly expensive operation. A lot of optimization has gone into HarfBuzz, but it’s still potentially a major contribution to overall layout time. The Web has struggled with this. For a long time, Chrome had both a “simple path” and a “complex path”, where shaping was disabled in the simple path. This degrades the experience and exposes this detail to users. So a few years ago Chrome implemented a word cache to accelerate the complex path, making it suitable for all use, and the simple path was removed in October 2016. All this is described in a Unicode presentation on Chrome text (PDF).

Similarly, the design of skribo will include a word cache. This should be transparent to most users. There will be careful attention to the design of the cache key, as the locale, OpenType features, and other style attributes need to be included along with the text, and complex data structures can be a significant performance issue in hashtable-based caches.

Out of scope

A number of problems are best handled at a higher level and are out of scope for this library:

-

Paragraph level formatting including line breaking.

-

Hyphenation.

-

Representation of rich text.

-

BiDi.

Many of these problems are solved by comparable platform text libraries such as DirectWrite and CoreText. I can imagine a higher level text layout crate that solves some of these problems, but for the time being this would need to be a community effort, I am not driving it as part of the skribo effort.

Inspirations

The scope of skribo is similar to pango, which is well-established in the free software world. However, its implementation will hew even more closely to Minikin, the low-level text layout library in Android. I’m biased of course, having written the first version of minikin, but I think there are many good reasons to use it as a basis, and am not alone; the libtxt layout engine used by Flutter is also based on a fork of Minikin.

Since one of the main use cases is web layout, existing open source implementations of Web layout, in Chrome (Blink) and Firefox (Gecko) will also be major sources.

What next?

I’ll be putting together a requirements document, then a design document. There’s a bit more detail on the project roadmap. I really want feedback on both of those, especially from potential users of the library. Then, over the next few weeks I will be intensively prototyping and refining the design.

This project is explicitly intended to teach and engage the community, rather than just being a black-box chunk of code. As I work, I expect to write a series of blog posts that explains problems in text layout that I’m solving. So a good way to follow the work is this blog. Feel free to ask questions also!