Font fallback deep dive

One of the main functions of skribo is “font fallback,” or choosing fonts to render an arbitrary string of text. This post is a deep dive into the topic, motivating the problem and explaining the approaches to solve it.

When buying fully into the platform’s text stack, font fallback is usually handled transparently. But when doing the layout ourselves, as is done in skribo (and as is generally necessary in Web browsers), we have to query deeply into the system to find the fonts.

To some extent, this blog post is explaining what’s going on in font-kit#37. Feel free to dig into that issue for more detail, or of course if you’d like to help out.

There are two crates involved in this work: font-kit wraps the system functions for enumerating and loading fonts, and skribo does text layout using fonts obtained from font-kit; skribo contains no platform-specific code.

What is font fallback?

No one font can cover all of Unicode, so text stacks rely on a patchwork, each of which covers some subset of scripts. A typical modern system has around 30 to 80 such fonts. Depending on the scripts used, a string might then require a bunch of different fonts to render. The problem of font fallback is to choose the fonts needed. That breaks down into the following main subproblems:

-

Determine (from the sytem) which fonts are available.

-

Determine, based on the string and the Unicode coverage of those fonts, which fonts to use.

-

When multiple fonts have Unicode coverage, choose the best.

That last bit is especially complex, as we’ll see. The major complications are:

-

Resolve Han unification, or more generally, prioritize based on locale.

-

Try to find a font that matches the style of the primary font.

Han unification

One thing that makes font choice particularly tricky is Han unification. Han unification was a deliberate choice by the Unicode consortium, probably motivated by the desire to make Unicode 1.0 fit in a 16 bit space, to reuse the same code point for ideographs shared by multiple scripts. A rough analogy is to use the same code point to encode Latin capital A and Greek capital alpha (“A” and “Α”). These might render the same or differently, depending on font choices. Similarly for CJK languages, there is a preference based on the language. If this preference is not respected, the text is still readable, but will look wrong. Getting Han unification right is a requirement for a modern text stack.

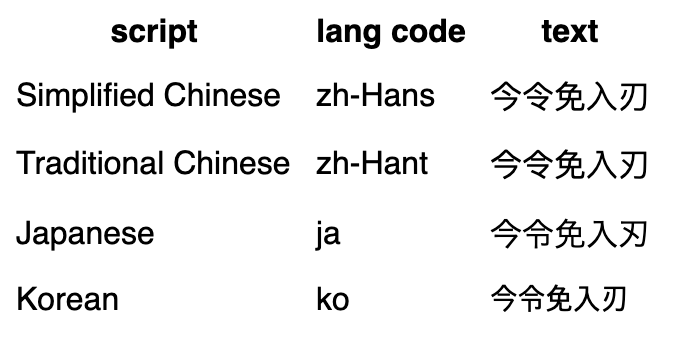

In the following example, the text is the same sequence of Unicode code points. Only the locale is set differently, and this has significant effect on the rendering.

An immediate consequence is that code point is not adequate for choosing a font, the locale must be an input as well. In HTML, locale can be set explicitly through the “lang” attribute. Failing that, a number of heuristics determine it, and in the last resort the system locale settings.

Another consequence is that a fallback font set can’t be just a list of fonts. There must at the least be metadata indicating language preference for Han unification (and in general choosing between alternate fonts based on language, though CJK is the most prominent case).

Finding the system fonts

At the core of font fallback is finding the system fonts suitable for the fallback chain. Note that in some cases this might not be necesary: it’s possible to bundle a high quality set of free fonts such as the Noto fonts, and more are being developed. That would give consistent rendering across platforms and avoid the need to query the system. But it’s a large download (tens of MB at least, more if more styles and weights are desired), so most of the time we want to get the fonts from the system.

There is no standard way to do this. Most platforms want you to buy in to their text stacks completely. Yet, largely motivated by Web browsers, there’s usually a way to get to the fallback fonts that’s not a complete hack. Of course, a complete hack is sometimes viable, you can just hard-code a list of fonts by system, along with knowledge of their CJK preferences.

The methods for finding fallback fonts vary by system, and within a system vary by time; often methods more suitable to Web use cases are available only in newer versions.

Windows

For Windows 8.1 and later, there is a pretty good API for finding the fallback fonts: the IDWriteFontFallback interface. This is a query by string, so it will need to be queried often, and it is difficult to cache the results. A good feature is that it doesn’t bother with unused fonts.

On older versions of Windows, there are a number of approaches, probably the best is to do layout for the string using the platform renderer, and then use a custom “renderer” that doesn’t actually render, but instead collects references to the fonts. Firefox does a version of this. Chrome does something similar but uses the older Uniscribe as well (this is compatible all the way back to XP).

macOS

It would be too much to ask for other platforms to provide a similar interface. The best way to find fallback fonts on macOS is CTFontCopyDefaultCascadeListForLanguages, which provides a list of fonts. To handle Han unification, it accepts a locale, so it will order the CJK fonts with the preferred language first. This API is not well-documented, but is fairly widely used.

Most of the time an app uses only one locale. In that case, it’s possible to call this function once and retain the results. It is very unusual to use more than a handful of unique locales. The flip side, though, is that you get dozens of fonts back and have to analyze them for Unicode coverage.

Linux / Fontconfig

I haven’t researched this as much as the others, but already I see some big problems. The Fontconfig API is rich enough to enumerate the fallback fonts, and contains language metadata, but it seems to me that at least Debian simply doesn’t have a correct config. I’ve found a number of blog posts (Tuning Fontconfig, Ubuntu better CJK, Picking CJK fonts) explaining how users can tweak their configs, but this seems like it shouldn’t be necessary. I also haven’t done a survey of distros other than Debian.

Meanwhile, it seems that browsers work around this by hardcoding the names of common CJK fonts at least, which in turn reduces the pressure to fix the configs - things kinda work most of the time, as is typical for Linux.

This is an area where I would love some help, both to figure out the best way to use existing infrastructure, and also to drive improvements in the default configs of distros.

Android

Android is a platform with not one but two different mechanisms. The classic mechanism is a fonts.xml file which lists out all the fonts along with their preferred language. That’s enough data to make this work. Probably one of the easiest and most efficient ways to adapt it is to provide the same interface as macOS above, then you just get a list of fonts appropriately prioritized for the locale.

But at the top of the fonts.xml file is a scary warning that it is going away in “the next release”. There’s a new API called SystemFonts, for which documentation is available for the Java but not yet NDK version. It’s likely that there will be an “itemize” method that will behave similarly as the MapCharacters method on recent Windows.

So the approach is to check version and do one or the other.

Performance considerations

These fallback queries can be expensive, so it’s important to minimize their impact. The two major approaches each have their challenges.

When the platform does itemization (as in Windows and new Android), you get fonts back, but no obvious way to tell that it’s the same font as a previous query. This is important for reuse of resources derived from a font, such as rendered glyphs.

For this purpose, Skia implements a unique ID per font, but its implementation is heuristic - in particular, it would be pretty easy to trick it by construction of malicious fonts. As far as I know, there’s no reliable way to do this on Windows, and we’ll see about Android. It’s possible we can use pointer equality for system fonts. I’m still looking into it; font-kit#40 tracks that work.

When the platform gives a list of suitable fonts (as in macOS and old Android), the major problem is digging through the fonts to determine which actually have the right Unicode coverage. It’s important to avoid copying font data, otherwise loading those fonts could take tens of MB of RAM, and quite a bit of time for allocating, copying, and analysis.

Conclusion

I’m spending more time on font fallback than I originally planned. That said, I think I’m on track to largely solve it, and hopeful that this will be a very useful resource for the Rust ecosystem. I think the general problem of making abstractions for platform services is one of the main areas in Rust that needs work now, and one of the great potential strengths of the language - most other languages either aren’t suitable for performant, low level work, or have gaps in their platform coverage, or both.

In investigating the issue, I’ve read lots of open source code, especially Qt, Blink, and Gecko. A lot of the knowledge around text is arcane, but it is out there in the form of working code.

Thanks again to the Servo people for supporting this work.