piet-gpu progress report

This post is an update to 2D Graphics on Modern GPU, just over a year ago. How time flies!

That post set out a vision of rendering 2D graphics on a GPU, using compute kernels rather than the rasterization pipeline, and offloading as much work as possible from the CPU to the GPU. It was also a rough research prototype, and I’ve spent some time trying to improve it in various ways. This blog post represents a checkpoint of that work - it’s still a research prototype, but improved.

One of the limitations of that prototype is that it was implemented in Metal, which was chosen for ease of development, but is challenging to port to other APIs. I’ve spent considerable time in the last year exploring issues around portable, advanced GPU programming, and among other things gave a talk entitled A taste of GPU compute. As part of the evolution of the work, the new prototype is in Vulkan with the compute kernels written in GLSL.

This blog post represents a checkpoint of the work; the code is in piet-gpu#15. Some aspects are very promising indeed, in particular the performance of “fine rasterization.” It is quite challenging to efficiently produce tiles for fine rasterization given a high-level scene representation, and this snapshot does not perform as well as I’d like. I am now exploring a new approach, and will post an update on that soon.

Even so, there is enough progress that I think it’s worthwhile to post an update now.

Infrastructure work

The new prototype is written on top of Vulkan, with the compute kernels written in GLSL. In addition, there’s an abstraction layer, inspired by gfx-hal, which provides a path for running on other graphics APIs.

Why not just gfx-hal? There are basically two reasons. First, I wanted to be able to experiment with the newest and freshest Vulkan features, including all the subgroup operations, control over subgroup size, etc. Many of these features are not yet available in gfx-hal. Second, for this use case, it makes sense to compile and optimize the compute kernels at compile time, rather than have a runtime pipeline. The total amount of code needed to just run a compute kernel is on the order of 1000 lines of code.

We’re looking to WebGPU for the future, and hope that it will be fairly straightforward to migrate Vulkan and GLSL code to that. Essentially we’re waiting for WebGPU to become more mature.

One of the modules in piet-gpu is a tool that generates GLSL code to read and write Rust-like structs and enums. The code ends up being a lot more readable than addressing big arrays of uint by hand, and in particular it’s easy to share data between Rust and GPU, especially important for the scene encoding.

Static, dynamic, and layered content

What kind of content is being rendered? It matters, more so for GPU than for CPU rendering.

At one extreme, we have fully static content, which might be rendered with different transforms (certainly in the case of 3D). In this case, it makes sense to do expensive precomputation on the content, optimized for random access traversal while rendering. Static content of this type often shows up in games.

At the other extreme, the 2D scene is generated from scratch every frame, and might share nothing with the previous frame. Precomputation just adds to the frame time, so the emphasis must be on getting the scene into the pipeline as quickly as possible. A good example of this type of content is scientific visualization.

In the middle is rendering for UI. Most frames resemble the previous frame, maybe with some transformations of some of the scene (for example, scrolling a window), maybe with some animation of parameters such as alpha opacity. Of course, some of the time the changes might be more dynamic, and it’s important not to add to the latency of creating a new view and instantiating all its resources. A major approach to improving the performance in this use case is layers.

Text rendering also has this mixed nature; the text itself is dynamic, but often it’s possible to precompute the font. Signed distance fields are a very popular approach for text rendering in games, but the approach has significant drawbacks, including RAM usage and challenges representing fine detail (as is needed for very thin font weights, for example).

Precomputation

Let’s look at precomputation in more detail. Much of the literature on GPU rendering assumes that an expensive precomputation pass is practical, and this pass often involves very sophisticated data structures. For example, Massively-Parallel Vector Graphics cites a precomputation time for the classic Ghostscript tiger image of 31.04ms, which destroys any hope of using the technique for fully dynamic applications. Random-Access Rendering of General Vector Graphics is similar, reporting 440ms for encoding (though on less powerful hardware of the time).

Another concern for precomputation is the memory requirements; the sophisticated data structures, specialized for random access, often take a lot more space than the source. For example, RAVG cites 428k for the encoded representation, as opposed to 62k for the tiger’s SVG source.

Similar concerns apply to fonts. Multi-channel signed distance fields are very appealing because of the speed of rendering and ease of integration into game pipelines, but the total storage requirement for a set of international fonts (especially CJK) is nontrivial, as well as the problems with fine details.

The Slug library is very polished solution to vector font rendering, and also relies on precomputation, computing a triangulated convex polygon enclosing the glyph shape and sorting the outlines so they can efficiently be traversed from a fragment shader. A quick test of slugfont on Inconsolata Regular generates a 486k file from a 105k input.

A particular interest of mine is variable fonts, and especially the ability to vary the parameters dynamically, either as an animation or microtypography. Such applications are not compatible with precomputation and require a more dynamic pipeline. I fully admit this is advanced, and if you’re just trying to ship a game (also where a few megabytes more of font data will barely be noticed among the assets), it’s easiest to just not bother.

Flattening

In the current piet-gpu pipeline, paths, made from lines, quadratic Bézier segments, and cubic Bézier segments, are flattened to polylines before being encoded and uploaded to the GPU. The flattening depends on the zoom factor; too coarse generates visible artifacts, and too fine is wasteful further down the pipeline (though it would certainly be possible to apply an adaptive strategy where a flattening result would be retained for a range of zoom factors).

The flattening algorithm is very sophisticated, and I hope to do either a blog post or a journal paper on the full version. I blogged previously about flattening quadratic Béziers, but the new version has a couple of refinements: it works on cubics as well, and it also has improved handling of cusps. You can play with an interactive JavaScript version or look at the Rust implementation.

The time to flatten and encode the tiger is about 1.9ms, making it barely suitable for dynamic use. However, there’s lots of room to improve. This is scalar, single-threaded code, and even CPU-side it could be optimized with SIMD and scaled to use multiple cores.

Even with single-threaded scalar code, flattening time is competitive with Pathfinder, which takes about 3ms to flatten, tile, and encode drawing commands (using multithreaded, SIMD optimized code, though further optimization is certainly possible). However, it is not suitable for interactive use on extremely complex scenes. For the paris-30k example, piet-gpu flattening and encoding takes about 68ms.

Ultimately, flattening should be moved to the GPU. The algorithm is designed so it can be evaluated in parallel (unlike recursive flattening and the Precise Flattening of Cubic Bézier Segments work). Flattening on GPU is especially important for font rendering, as it would allow rendering at arbitrary scale without reuploading the outline data.

One open question for flattening is exactly where in the pipeline it should be applied. It’s possible to run it before the existing pipeline, during tile generation, or preserve at least quadratic Béziers all the way through the pipeline to the pixel rendering stage, as is done in much of the GPU rendering literature. Figuring out the best strategy will mean implementing and measuring a lot of different approaches.

The piet-gpu architecture

The current piet-gpu architecture is a relatively simple pipeline of compute kernels. A general theme is that each stage in the pipeline is responsible for a larger geometric area, and distributes pieces of work to smaller tiles for the successive stages.

The first stage is on CPU and is the encoding of the scene to a buffer which will then be uploaded to the GPU. This encoding is vaguely reminiscent of flatbuffers, and is driven by “derive” code that automatically generates both Rust-side encoding and GLSL headers to access the data. As discussed in considerably more detail below, the encoding of curves also involves flattening, but that’s not essential to the architecture. After the encoded scene buffer is uploaded, successive stages run on the GPU.

The first compute kernel has a fairly simple job. It traverses the input scene graph and then generates a list of “instances” (references to leaf nodes in the scene graph, with transform) for each “tile group” (currently a 512x16 region). It uses bounding boxes (encoded along with nodes by the CPU) to cull.

The second compute kernel is specialized to vector paths. It takes the instances of vector stroke and fill items, and for each 16x16 tile generates a list of segments for that item for that tile. For fills, it also computes the “backdrop”, which is important for filling interior tiles of a large shape even when no segments cross that tile.

The third compute kernel is responsible for generating a per-tile command list (sometimes referred to as a “tape,” and called a “cell stream” in the RAVG terminology). There’s generally a straightforward mapping from instances to commands, but this kernel can do other optimizations. For example, a solid opaque tile can “reset” the output stream, removing drawing commands that would be completely occluded by that tile.

The fourth compute kernel reads its per-tile command list and generates all the pixels in a 16x16 tile, writing them to the output image. This stage is effectively identical to the pixel shader in the RAVG paper, but with one small twist. Because it’s a compute kernel, each thread can read the input commands and generate a chunk of pixels (currently 8), amortizing the nontrivial cost of reading the tape over more more than just one pixel. Of course it would be possible to run this in a fragment shader if compute were not available.

These kernels are relatively straightforward, but essentially brute-force. A common theme is that all threads in a workgroup cooperate to read the input in parallel, then there is a “block shuffle” approach to distribute that work to the individual threads responsible for writing out work for smaller subregions. I described an approach based on 32x32 boolean matrix transpose in my Taste of GPU Compute talk, but in practice we find that using atomic operations to assign work is slightly faster.

Layers

As mentioned above, in a UI most of the time, most of the content in the frame is the same as the last frame. Some UI frameworks (imgui in particular) just traverse the entire UI state and draw every time, but most do something to cut down on work done.

The main mechanism is some kind of layer, an object that retains the appearance of a widget or subview. In Apple toolkits, this layer (CALayer in particular) is a GPU-resident texture (image). This design made sense in the days of the iPhone 1, where the GPU was just barely powerful enough to composite the final surface from multiple such images at 60fps, but there are significant drawbacks to this approach. Applications need to avoid creating too many layers, as that can consume a huge amount of GPU memory. There’s also increased latency when content changes dynamically, as it needs to be re-rendered and re-uploaded before being composited. But the approach does work. It also leads to a certain aesthetic, emphasizing the animations that can be efficiently expressed (translation and alpha fading) over others that would require re-rendering.

Flutter has a more sophisticated approach, explained well in the video Flutter’s Rendering Pipeline. There, a layer can be backed by either a recorded display list (SkPicture under the hood) or a texture, with a heuristic to decide which one. My understanding is that SkPicture is implemented by recording drawing commands into a CPU-side buffer, then playing them back much as if they had been issued in immediate mode. Thus, it’s primarily a technique to reduce time spent in the scripting layer, rather than a speedup in the rendering pipeline per se. The Android RenderNode is similar (and is used extensively in Jetpack Compose).

One of the design goals in piet-gpu is to move this mechanism farther down the pipeline, so that a fragment of the scene graph can be retained GPU-side, and the layer abstraction exposed to the UI is a handle to GPU-resident resources. Note that this isn’t very different than the way images are already handled in virtually every modern rendering system.

The layer concept is also valid for many art and design applications, as well as maps. It’s extremely common to organize the document or artwork into layers, and then modifications can be made to just one layer.

This mechanism is not yet wired up end-to-end, as it requires more work to do asynchronous resource management (including better allocation of GPU buffers), but the experimental results do show that the potential savings are significant; re-encoding and re-uploading of the scene graph to the GPU is a substantial fraction of the total time, so avoiding it is a big gain.

Doing flattening GPU-side would make the layer concept even more powerful, as it enables zoom (and potentially other transformations) of layers without re-upload, also avoiding the blurring that happens when bitmap textures are scaled.

CPU vs GPU

If the same work can be done on either CPU or GPU, then it’s sometimes a complex tradeoff which is best. The goal of piet-gpu is for GPU-side computation to be so much faster than CPU that it’s basically always a win. But sometimes optimizing is easier CPU side. Which is better, then, depends on context.

In a game, the GPU might be spending every possible GFLOP drawing a beautiful, detailed 3D world, of which the 2D layer might be a small but necessary concern. If the CPU is running a fairly lightweight load, then having it run most of the 2D rendering pipeline, just save getting the final pixels on the screen, might make sense.

Again, the assumptions driving piet-gpu are primarily for UI, where latency is the primary concern, and keeping work off the main UI thread is a major part of the strategy to avoid jank. Under this set of assumptions, offloading any work from the CPU to the GPU is a win, even if the GPU is not super-efficient, as long as the whole scene comes in under the 16ms frame budget (or 8ms, now that 120Hz displays are becoming more mainstream). The current piet-gpu codebase addresses this well, and will do so even better as flattening is also moved to GPU.

The relative tradeoff is also affected by the speed of the graphics card. Single threaded CPU performance is basically stuck now, but GPUs will get faster and faster; already we’re seeing Intel integrated GPU go from anemic to serious competitors to low-end discrete graphics cards.

Performance

I’m not yet satisfied with the performance of piet-gpu, yet there are aspects of it which are very encouraging. In particular, I feel that the final stage of the pipeline (sometimes called “fine rasterization”) is very fast. Even though it’s producing a huge volume of pixels per second, this stage only takes about 1/4 to 1/3 of the total piet-gpu time. It’s tantalizing to imagine what performance could look like if the cost of producing tiles for fine rasterization was further reduced.

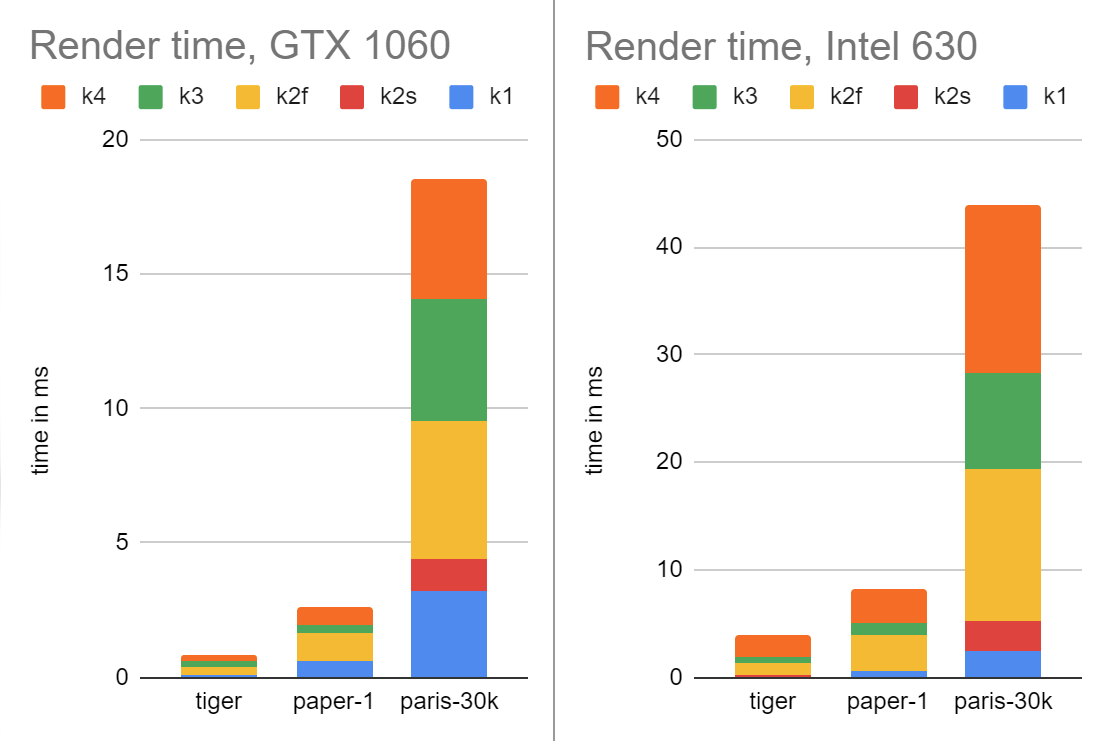

For performance testing, I’m using 3 samples from the Massively-Parallel Vector Graphics suite. Tiger is the well-known Ghostscript tiger, almost a “hello world” of 2D graphics rendering, paper-1 is a text-heavy workload, and paris-30k is a highly detailed map. Note that the rendering of paris-30k is not fully correct, and in particular all strokes are rendered with the same style (round ends and caps and no dashing). It’s probably reasonable to budget 30% additional time to get these stroke styles right, as they can significantly increase the number of path segments, but I’m also interested in ways to optimize this further. Also keep in mind, these numbers are GPU time only, and don’t include the cost of flattening in particular (currently on CPU).

With that said, here’s a chart of the performance, broken down by pipeline stage. Here, k4 is “kernel 4”, or fine rasterization, the stage that actually produces the pixels.

These measurements are done on a four-core i7-7700HQ processor; with more cores, the CPU time would scale down, and vice versa, as Pathfinder is very effective in exploiting multithreading.

At some point, I’d like to do a much more thorough performance comparison, but doing performance measurement of GPU is surprisingly difficult, so I want to take the time to do it properly. In the meantime, here are rough numbers from the current master version of Pathfinder running on GTX 1060: tiger 2.3ms (of which GPU is 0.7), paper-1 7.3ms (GPU 1.1ms), and paris-30k 83ms (GPU 15.5ms). On Intel 630, the total time is only slightly larger, with the GPU taking roughly the same amount of time as CPU. Also keep in mind, these figures do include flattening, and see below for an update about Pathfinder performance.

Prospects

I have basically felt driven as I have engaged this research, as I enjoy mastering the dramatically greater compute power available through GPU. But the work has been going more slowly than I would like, in part because the tools available for portable GPU compute are so primitive. The current state of piet-gpu is a research codebase that provides evidence for the ideas and techniques, but is not usable in production.

I would like for piet-gpu to become production-quality, but am not sure whether or when that will happen. Some pieces, especially fallbacks for when advanced GPU compute features are not available (and working around the inevitable GPU driver bugs, of which I have encountered at least 4 so far), require a lot of code and work, as does the obsessive tuning and micro-optimization endemic to developing for real GPU hardware.

Another extremely good outcome for this work would be for it to flow into a high quality open-source rendering project. One of the best candidates for that is Pathfinder, which has been gaining momentum and has also incorporated some of my ideas. One of the appealing aspects of Pathfinder is its “mix and match” architecture, where some stages might be done on CPU and others on GPU, and the final pixel rendering can be done in either the rasterization or compute pipeline, the choice made based on compatibility and observed performance. In fact, since the first draft of this blog post, I’ve been working closely with Patrick, sharing ideas back and forth, and there is now a compute branch of Pathfinder with some encouraging performance numbers. You’ll hear more about that soon.

Thanks to Brian Merchant for work on various parts of piet-gpu, msiglreith for help with Vulkan, and Patrick Walton for many conversations about the best way to render 2D graphics.

There was some discussion on /r/rust.